Class notes are an excellent way for you to remain connected to your class officers and classmates. Here you can view and submit notes and photos that fall into several categories. To submit your class note, please click the “ADD MY NOTE” button on the right side of your screen. If you wish to submit an Obituary for a classmate or family member, please click “ADD MY NOTE” and use the In Memoriam category. Obituaries submitted after August 7, 2021, will be displayed on this page by clicking the “In Memoriam” category. To view a more complete list of deceased classmates, please click here. Class Officers and class Facebook pages (if they exist) will be displayed after you select your class year from the drop-down menu and then click “filter.” All class notes associated with the class year will be displayed after you select the specific class year. To view all class notes that have been submitted since August 7, 2021, select “Any” for the year. All the class notes and photos published in Wooster magazine are drawn from those shared online here; no further submission is required.

Add My Note

Nancy Caldwell

Nancy (Nana) Anne Caldwell, of Pasadena, passed peacefully among family and friends on Friday, August 13, 2021. The daughter of Nancy and Powell Awbrey she was born July 8, 1940 in Parsons, Kansas. Her childhood days were filled with family gatherings, church, friends, trips and entertaining. She earned her B.A. with Honors in Political Science from the College of Wooster. And, earned her M.A. and Marriage and Family Counselor license in the State of California.

Nancy met her future husband, Larry Caldwell while attending the College of Wooster. She lived in London for two periods where she became a great fan of brass rubbing in the days when that was still done partly by standing on rickety wooden ladders, in cold stone country churches. She also lived, with her young family, in McClean and Reston, Virginia, where she took up quilting and touring our nations early history with her young sons and husband. The couple eventually settled in Altadena, California, where Nancy raised three children: Stuart, Ethan and Trevor Caldwell.

Nancy taught middle school in Tewksbury, Massachusetts and worked for a number of years at J. Herbert Halls and Valle’s Jewelers in Pasadena. In every position she held she was known as a true people person. She had the rare gift of remembering who she met and personal details about them. She was a people person at heart.

Nancy was active in the Presbyterian Church throughout her life. She taught Sunday School, served as Deacon and as a Ruling Elder. She was unobtrusively devoted to God, developed deep friendships through congregation, and advocated for an inclusive church. The mother of boys and sister of brothers, she could hold her own on a hike or watching a basketball game but was quick to make female friends and dote on her granddaughters, nieces, and the daughters of others, given the chance. Forever a child of the Sunflower State, she would light up when presented with her favorite flower. She and her family spent many summers making memories in the lakes, rivers, and mountains of the Colorado Rockies, where she returned with frequency as a devoted daughter to her elder mother and companion to her brother in his later years.

Part-time family historian and a full-time nurturer of others, her legacy includes dynamic and successful grown children and their growing families, multi-generational friendships, and many hearts touched. Nancy was a devoted mother to her three sons, the joy of her life; and loved being “Nana” to her adored grandchildren. She was a passionate basketball fan, rooting for her sons at La Salle High School and at Occidental College, but also the Kansas Jayhawks and the Los Angeles Lakers. She was a loyal friend throughout her life, always making friends readily and easily. She enjoyed entertaining and many close and lasting friendships. She is survived by her three sons, Stuart Caldwell, Ethan Caldwell and Trevor Caldwell; her honorary son, Jeff Randall; her loyal daughters in law, Briana, Lisa and Loriann Caldwell; her seven grandchildren; and her many friends.

Her brothers, Stuart and John predeceased her. Services will be held on Saturday, September 11, 2021 at 2:00 pm at the Pasadena Presbyterian Church. In lieu of flowers the family requests that donations be made to the Pasadena Presbyterian Church or the Ranch House, Memory Care at the Monte Vista Grove Homes in Pasadena, California. Published by Whittier Daily News on Sep. 5, 2021.

Eleanor Wagner

Audiologist, author, activist, artist, and loving mother and grandmother, Eleanor “Elly” Ruth Wagner was born in Pittsburgh, PA on Sept. 17, 1941. Raised in Houston, PA, Elly graduated with a bachelor’s degree from the College of Wooster and a master’s degree from the University of Illinois. In 1965, while registering voters in Montgomery, AL, she attended a sermon by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. that inspired her lifelong activism. She worked tirelessly to make the world a better place, consistently championing the causes of social justice, voting rights, LGBTQ+ rights, non-violence, and climate stabilization and sustainability. In 1971, she moved to Edina where she made her home, raised her children, and cultivated the garden that was her pride and joy later in life. She worked as an audiologist at Park Nicollet Medical Center for over 40 years, specializing in patients with tinnitus.

Elly was an author, publishing 3 books including Lavender Reflections, a book of affirmations for lesbians and gay men, published in 1995. Her other professions included photography, gardening herbs and flowers, crafting, and she was a vendor and then president of the Hopkins Farmer’s Market. Elly was a skilled musician who brought people together through music and song. She was active in her local community, including the Lyndale United Church of Christ, Grandmothers for Peace, MN Herb Society, and several writer and book groups.

She died after a long battle with pancreatic cancer on Sept. 23, 2021 at home, surrounded by family and friends. Predeceased by her parents Homer and Louise and brothers David and William, she is survived by her sister Lois, brother Paul, long-term friend Kathy, sons Glydewell (Cynthia) and Keith (Jennifer), and 4 grandchildren. A memorial service is scheduled for October 9, 2021 (details at summitfuneralandcremation.com). In lieu of flowers, please make tributes to Lyndale UCC on Elly’s behalf.

Janet Senne

Janet Senne, of Sandusky, a woman of many interests and involvements, died peacefully at Portland Place December 3. She was 94 years old. She was born January 8, 1921 to Francis and Norma Kuhn in Tiffin, Ohio. A graduate of Heidelberg University in Tiffin, she originally came to Sandusky for work as a draftsman during World War Two. Following her marriage to Donald on May 1, 1949, she turned her attention to child rearing and community engagements. As a continuous member of Grace Episcopal Church, she served as a volunteer and longtime manager of its Thrift Shop. With the help of supportive friends, she actively attended services until recent weeks. Janet’s involvement in local cultural and historical groups was widespread and enduring. She was a multi decade member of the Erie County Historical Society. And, in no particular order of priority, was also a longstanding member of AAUW, the Old House Guild, the Follett House Museum, Puppeteers of America, and Serving Our Seniors.

In creative pursuit of her historic interests, she often provided live character portrayals of notable women in church and local history. Additionally, for many years she manned and promoted the Historical Pavilion at the Erie County Fairgrounds, and assisted Don delivering Meals on Wheels. Still further, she was a Campfire Girl leader and avid puppeteer, providing countless performances for church and community groups.

She is lovingly survived by her son, Steven (Judi) Senne; son-in-law, Tom Stuck; grandchildren, Jolyn (Blair) Russell, Jacob (Elisha) Stuck, Michael (Amy) Stuck, Ann (Craig) Murray and Rachel Stuck; great-grandchildren Keane, Syden and Palen Russell; Henry Stuck; Nolan, Graham, and Paige Murray She was preceded in death this year by Donald Senne, her husband of 65 years, a daughter, Mary Stuck, in 2006, and brothers, Robert Kuhn and James Kuhn A memorial service will be 10:00 a.m. Friday, December 11, 2015, in Grace Episcopal Church, 315 Wayne St., Sandusky. The Rev. Jan Smith Wood will officiate. Memorial contributions in Janet’s name may be made to Grace Episcopal Church, or to Serving our Seniors, 310 E. Boalt St., Sandusky, OH 44870. Toft Funeral Home & Crematory, 2001 Columbus Ave., Sandusky, is handling the arrangements. Condolences and gifts of sympathy may be made to the family by visiting www.toftfh.com.

Ann Coffman Hunter

Hello from Ann Coffman Hunter. Last spring, Dick and I moved to a retirement community just north of Baltimore. Fortunately, our house sold in three days, but the whole process, which would have been tough under normal circumstances, was grueling, especially since Dick was still recovering from his extensive back surgery in January. However, it was all worth it, because we love Broadmead, which was started by Quakers and has mostly one story homes and a huge campus with hiking trails. I have plenty of room to garden and get to talk to lots of people who stop by when I’m happily digging in the dirt.

During downsizing I read all the letters I had written to my parents; it was like reading an epistolary novel. I learned that it had taken “a village” (second floor Babcock) to get my IS in, one day late. I remembered that a few people had helped me, but I had told my parents about every single person who stopped by to type, proofread, collate, whatever I needed. Though you may not remember, I just want to tell you all how grateful I am for such kind and helpful friends.

We’ve had it bit of contact with Elden Schneider and Lydia Robertson Brown locally, and also with Dori Hale, but we will be glad when we can see more of you, virtually or in person.

Patricia Strubbe

I’m retired twice! I began work as a Children’s Librarian in my hometown library, Herrick Memorial Library, in August 1973. Grew up in Wellington, Ohio, from the age of 10. Working with kids and books was inevitable, my two loves. I continued working there for 29 years – many generations! Retired for one year to see what I wanted to do ‘when I grew up!’ For 9 months I attended nursery school, volunteering then assisting part time. Had to get back to books and people. Began work in 2002 as Children’s Associate in Ashland, Ohio, public library. Retired in July 2011, partly because I realized it was getting hard to keep up with the kids! After about 3 years, I couldn’t hike or maintain my flowerbeds anymore. Too hard physically to bend, sun & heat intolerance. Turns out I have Sjogren’s Syndrome, probably began in childhood, including fibromyalgia, couple other autoimmune disorders. What a way to spend retirement – indoors or in shade, puzzle books, music CDs, etc. Facebook has become a life saver. Catching up with so many parents & kids from libraries, former school friends, aunt & 3 cousins; siblings on west coast seem to be involved with themselves and partners. So, here I sit typing to you! That’s my life in a nutshell since COW graduation!

David G. Johnston

David G. Johnston passed away unexpectedly on September 23,2021 in Pittsburgh, PA at the age of 62. David will be remembered for his warmth, kind spirit and generous compassion for others, and his love of family. Although he didn’t have a lot of material goods, he shared his time and energy with anyone in need.

David was born to Marion (Northup) and James R. Johnston in Sewickley, PA to where he developed an abiding love for Pittsburgh. He was an avid fan of all the Pittsburgh sports teams, starting with the Pirates and his admiration for Roberto Clemente. David then lived in Carlisle PA where he was a member of the Second Presbyterian Church. Following his father’s footsteps, he participated in scouting and camping and developed his love of nature – including a trip to Mexico to see the solar eclipse.

He graduated from the College of Wooster where he found life-long friends. David moved to the Boston area where he lived for over a decade, making many friends. Throughout that decade, he rarely missed a weekend volunteering at his local church food bank. Before leaving Boston, David graduated from Tufts University with a Master’s in Urban Planning and worked as a procurement specialist. In 1995, David returned to Pittsburgh where he continued this line of work for the county and the city and helped to raise his beloved twins, Martin and Emily.

Of all the qualities that David possessed, what has impacted those around him the most are his positive attitude and friendly disposition. He was amicable and easy-going; he could strike up a conversation with anyone – from the bus driver on his route to his work colleagues to the regular customers at the local diner. David was known for his strong tennis game with impossible serves. He was competitive in ping pong and volleyball, where he would dive into a creek to retrieve a wayward ball, all to make people laugh. He loved to tease his four sisters and was a good storyteller always finding the humor in human predicaments. He had a fierce love of dogs – even though his dogs were never well trained. He loved bluegrass music and enjoyed his nieces and nephews.

As a man of faith, he found his involvement with the East Liberty Presbyterian Church meaningful, serving as Deacon and volunteer. Because of his faith, he anticipated a happy reunion with his loved ones. He will be greatly missed. He is survived by his twin children Emily (Ryan) Provolt and Martin (Haley) Sasso, siblings Jennifer McKenna, Gail Viscome, Ann Johnston and Lucy Johnston-Walsh, 11 nieces and nephews and four great nieces and nephews.

A small service will be held starting at 11:30 Monday September 27 (including a zoom link on the website at the funeral home – D’Alessandro, 4522 Butler St., Pittsburgh PA) and another service later in the fall in Carlisle at Second Presbyterian Church. Zoom Info: Topic: Johnston Funeral Time: Sep 27, 2021 11:30 AM Eastern Time (US and Canada) Join Zoom Meeting, Meeting ID: 816 1584 1927. Find your local number: https://us02web.zoom.us/u/kWmYUBgDH To send flowers or a memorial gift to the family of David Glen Johnston please visit our Sympathy Store.

David M. Kinney

Dave Hay ’77, Rob Rutan ‘77, Dave Luken ’77 , Bob Dyer ’77 , Tom Farquhar ’77 , and Mike Kinney ’76 enjoying a 4 day rafting and camping trip on the Colorado River in Utah earlier in September. Other than hairlines and waistlines not much has changed.

John R. Luvaas

As a former contributor to this paper, Randy would have likely preferred to have his name appear as a byline in any other section of this rag. But here we are. On Tuesday, April 13, 2021, Randy Luvaas departed his earthly constraints and joined the angel band. He has ended his many battles with – you name it – including seven-bypass heart surgery and glioblastoma. Randy was born John Randall Luvaas on February 13, 1952 in Durham, North Carolina to Jay and Vera Lee (Hampson) Luvaas. After graduating from Meadville Area Senior High (1970) in Meadville, PA, he attended the College of Wooster (1974) where he studied literature because “if I’m going to do all that reading, I’m at least going to read something good.” Thereafter, his interest in writing led him to newspaper work, first for the Meadville Tribune, then, after relocating to the Pacific Northwest, to the Toppenish Review, where he was writer and editor. He then migrated to the Yakima Herald-Republic and concluded his newspaper career as editor and writer for Yakima Valley Publishing.

Randy was very active in and supportive of the Unitarian Universalist Church of Yakima. He loved the Pacific Northwest and spending time outdoors with his family. He made sure his son Riley explored the outdoors, read good books, had a baseball and soccer coach, grew up in UU principles and teachings, cursed the Yankees and grew accustomed to disappointment with the Seattle Mariners. We’re all looking forward to the M’s inevitable World Series victory to spite Randy for all his years of fandom.

Even though writing was his profession, music was his passion. He excelled at musical arranging, singing, and playing guitar in several bands, including the Yakima Fruit Tramps, the Jazzicians and Torrential Downpour. Randy is survived by his wife of 35 years, Janis (Miller), whom he met in Toppenish in 1982, but who grew up on the same street in their hometown of Meadville.

Randy would describe Janis as a long-suffering wife, which she was. But she remains eternally grateful for the love and laughter he gave her. He is also survived by his son Riley, who inherited all that was good in his father; sisters Karen Luvaas (Peter Kucera), Diane Buckius, and Amy Miller (Bill); and brother Eric Luvaas (Jennifer); brother-in-law Douglas Miller (Marilyn); numerous nieces, nephews and cousins; and many beloved and devoted friends. We are most grateful to those who shared his love of music, especially these last wonderful years with the Yakima Fruit Tramps.

A Remembrance Event will be held on Saturday, May 15th, at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Yakima, 225 North 2nd Street in Yakima, starting at 3:00 PM. Please come and share your memories of this great guy. Donations in Randy’s memory may be made to Justice Housing Yakima: https://donorbox.org/cottage-hill-village, because, there but for the grace of God go any of us. Brookside Funeral Home is caring for the family. Memories and condolences can be shared at www.brooksidefuneral.com. “I see my light come shining, From the west down to the east. Any day now, any day now, I shall be released.” (Bob Dylan)

David P. Hopkins

David Pearce Hopkins, 73, of Westminster, MD, passed away on Friday, May 28, 2021, in Carroll County, MD. Born on December 8, 1947, he was the son of the late Paul Albert and Jeanne Pearce Hopkins. David spent his life as an educator, with a career spanning over 50 years. Having worked at the Stony Brook School of Long Island, NY as a history teacher, and as a Baltimore County school psychologist. David was a well traveled man, having lived abroad in Germany and Greece. He dedicated his life to the teachings of patience, equity, and justice. Anyone who knew David knew of his love for trains having spent much of his childhood watching them from Radnor Station, how proud of his sons he was, his love for dogs, painting, and perhaps above all, his unshakable opinions on American politics. He will always be remembered for his kindness and his wisdom. Carrying on his legacy are his sons: Joshua and Benjamin Hopkins, and his siblings: Sydney Schnaars of Ohio and Tim Hopkins of Missouri. In the hopes of honoring David, the family asks that you donate to the Diabetes Research Institute. Memorial Services are private. Arrangements are by the ECKHARDT FUNERAL CHAPEL, P.A., Manchester, MD.

John Toerge

ROCKVILLE, Md. Oct. 1, 2021. John E. Toerge, DO is being recognized by Continental Who’s Who as a Trusted Physiatrist for his decades of outstanding work in the Medical field.

Dr. Toerge is the Owner and Medical Director at his private Physiatry practice, John E. Toerge DO LLC. Located in Rockville, MD, Dr. Toerge has been helping patients for over forty years. He believes that the best outcomes occur when patients are properly informed and actively involved in their treatment process. He works with patients who have diseases or injuries that affect their ability to move, and helps them to achieve the best outcomes possible.

Dr. Toerge additionally works as a Professor at Georgetown University. He is also proud to have been a crucial member of the development of the National Rehabilitation Hospital in Washington, DC.

To achieve his career in Physiatry, Dr. Toerge began his education at the College of Wooster, earning a Bachelor of Science degree in Biology. He then attended the Chicago College of Osteopathic Medicine at Midwestern University, earning his Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine degree. He then completed an internship at the Chicago Osteopathic Hospital and Medical Center. Dr. Toerge next took on a residency at Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. He then earned his board certification in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, becoming a Diplomat of the American Board of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, and the American Osteopathic Board of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation.

Awarded for his excellent work in the medical field, he has been recognized as a Finalist in the First Annual Humanist Award 1990; Top MD from Consumers Checkbook; Sigma Sigma Phi Honorary Osteopathic Fraternity; Diplomat American Osteopathic Board of Examiners; Recipient of the Employee of the Year Award National Rehabilitation Hospital/District of Columbia Hospital Association; Bethesda Magazine Top Doctor Award 2021, and awarded Super Doctor from SuperDoctors.com. Dr. Toerge is a Fellow and active member of the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation.

On a personal note, the doctor is an accomplished musician who plays trumpet and drums for the all-physician band “Feel So Good,” the “Village Jazz Band” (Dixieland), the “DC Brass Quintet,” and the trumpet quartet, “TJ3”.

Dr. Toerge would like to dedicate this honorable recognition to Henry Betts, MD, and Paul R. Meyer, Jr., MD, who were both his mentors during his training at Northwestern University.

For more information, visit www.johntoergedo.com.

SOURCE Continental Who’s Who

Related Links

Christopher B. Rainey

Oxford resident Christopher Boyd Rainey was a beloved husband, dad, Pappaw, teacher and coach. Rainey, 69, died Dec.12 after suffering a heart attack. Born on Sept. 17, 1951, in Canton, Ohio, Rainey attended North Canton Hoover High School before continuing his education at the College of Wooster. Upon graduating from Wooster in 1973, Rainey moved to Yellow Springs where he began his 35-year career with the Yellow Springs School District.

Throughout his tenure, Rainey touched the lives of thousands of students at both the middle school and high school levels. As a math teacher, he was twice honored with a Howard Post Award for Teacher of the Year. His impact, however, extended far beyond the classroom. He coached more than 40 teams in baseball, basketball, softball and tennis, and won numerous district, conference and league titles. In addition to being a teacher and coach, Rainey also spent time as Yellow Springs’ athletic director and assistant principal. He played an instrumental role in the creation of the Metro Buckeye Conference, later serving two terms as commissioner. While Rainey was a fan of all sports, he was most passionate about baseball. According to his family, Rainey was a devout Cleveland Indians fan, a ravenous historian and a meticulous baseball card collector. In college, Rainey was awarded a letter jacket for his work as the baseball team’s equipment manager, statistician and color announcer on the first local radio broadcast of a game. Later on, he got involved with the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR). Since becoming an SABR member in the late 1970s, Rainey had contributed biographies of more than 80 unnoted baseball players from the early 20th century.

He married Kathleen Steila on July 13, 1973. They had two children, Mark and Brian, and divorced in 1985. At home, Rainey raised two sons as a single father. “He was fun, firm and fair,” said Brian Rainey, one of his sons. “[He was] always willing to make a sacrifice for the needs of his two sons.” In 2010, Rainey married his wife, Janelle and moved to Oxford, where his wife had worked for Talawanda Schools. Together, they liked to attend Cobblestone Community Church, in Oxford, and spend time with their grandchildren. They enjoyed cooking, traveling and dining out at mom-and-pop restaurants. Because of her, he developed a taste for coffee. “They lived 10 happy years together, giddy like teenagers,” said Brian Rainey.

Rainey is preceded in death by a son, Mark S. Rainey, and his parents, Robert and Herta Rainey. In addition to his wife and son, he is survived by his brother, Lee Rainey; sister-in-law, Virginia Rainey; daughter-in-law, Amy Boblitt; three stepchildren and their spouses, and seven grandchildren. Funeral services will be held at a later date, according to his son. In lieu of flowers, donations can be made to a newly established Chris Rainey Memorial Scholarship fund via the Yellow Springs Community Foundation.

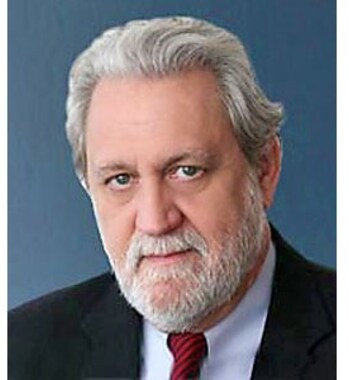

Gregory C. Postel

Postel Appointed UToledo President March 3, 2021 | News, UToday, Advancement, Alumni By Dr. Adrienne King Dr. Gregory Postel was named the 18th president of The University of Toledo during a special Board of Trustees meeting on Wednesday. The Board commended Postel for his tireless efforts since joining UToledo in the interim role last July. Board Chair Al Baker noted many of Postel’s accomplishments including successfully leading the safe reopening of campus during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since the beginning of fall semester, UToledo has navigated the pandemic utilizing the Rocket Prevention Principles best practices, a proactive surveillance testing strategy and transparent communication. UToledo’s reported positivity rate has remained below the state’s reported positivity rate since tracking began in August. In addition, Postel was recognized for the stabilization of hospital finances following a tumultuous year for The University of Toledo Medical Center exacerbated by the pandemic. Preliminary FY21 projections indicate a positive turnaround in revenue. The University’s growing research portfolio continues to grow with several recent multimillion dollar grants announced from the Department of Defense, NASA and NIH, to name just a few. The University’s year-to-date research funding numbers are on track based on last year’s goals.

Postel was actively involved in securing the institution’s second named college – the John B. and Lillian E. Neff College of Business and Innovation, which was announced in December. He has assisted with a number of other private gifts to support the University. “We are extremely grateful for Dr. Postel’s leadership during this challenging transition and want to commend all members of our campus community who have stepped up to realize these accomplishments,” Baker said. “Looking ahead, we know that we must continue this momentum if we are to realize our potential as a national, public research university where students obtain a world-class education and become part of a diverse community of leaders committed to improving the human condition in the region and the world.”

Postel has identified eight key initiatives and appointed campus-wide working groups focused on creating a solid foundation upon which to build future growth. The Board applauded Postel for addressing challenges head-on and noted that stable leadership is critical as the University moves forward. “Dr. Postel’s leadership has been instrumental in stabilizing the institution, but perhaps more importantly, he is actively preparing The University of Toledo for the upcoming Higher Learning Commission visit in November 2021,” Baker said. “After careful deliberation, including consultation with members of the University’s senior leadership team, deans and faculty senate representatives, the Board was honored to appoint Dr. Postel to this position.” The board unanimously approved a resolution to continue his service to UToledo through June 2025. “I am truly appreciative of and humbled by the vote of confidence from the Board of Trustees,” Postel said. “I have found The University of Toledo to be an outstanding institution committed to student success. I look forward to working collaboratively with the dedicated leaders across our campuses to continue our positive momentum and achieve UToledo’s full potential.”

Postel has more than 25 years of leadership experience with university operations, academic medical centers and clinical research, as well as university governance, teaching and research. Prior to joining UToledo, he served as the senior client partner representing healthcare services and higher education at Korn Ferry, a global organizational consulting firm. In addition to an accomplished career as an academic interventional neuroradiologist, Postel served 18 years as chair of the Department of Radiology at the UofL School of Medicine and held the positions of vice dean for clinical affairs and chair of the board at University Medical Center in Louisville. He was the founding board chair and later CEO of University of Louisville Physicians. Postel served as interim president of UofL in 2017-18 and also spent four years as its executive vice president for health affairs. A graduate of the College of Wooster and Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Postel completed a residency in radiology at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation and a fellowship in neuroradiology at the Mayo Clinic Foundation. He and his wife, Sally, have twin sons, Alex and Chris.

Michael Patterson

Another group holding weekly Zoom get together are a group of men of KX (Seventh Section) from 1973 – 1977. The group includes ‘73ers Dan Hyatt, Bill Henley, Dave “Tiny” Wilbur, and Rod Russell. Class of’74 members are Tim Fusco, Chris Nicely, Don Allman, and Brian Chisnell. From the Class of ‘75 are Denny Zeiters, Jay Schmidt, Gene Schindewolf, Mike “Poon” Patterson, Jim Clough, Robin Harbage, Dave Stenner, and “Easy” Ed Snyder. Representing the Class of ‘76 are Pat McLaughlin, Dave “Bird” Branfield, and Rick Hopkins and Dave Churchill is from the Class of ‘77. There are many exchanges of memories, some smack talk, and many laughs as pictures from long, long ago are produced! (note from me: the group contact is Bill Henley ‘73.)

Debbie Starr Branfield

Secretary, Class of 1976

Richard Cohoon

The Rev. Richard A. Cohoon moved on to greater glory on June 13, 2020 at the age of 90. He resided at Eagle Ridge Personal Care Home for the last seven years of his life. Father Cohoon was ordained priest in the Episcopal Diocese of Central Pennsylvania in 1954, and served parishes in Allentown and Lock Haven. He was preceded in death by wives Marjorie Morgan Cohoon and Diana Cohoon, and both of his children, Lowell and Janet. Richard is survived by his brother Walter (spouse Maxine) and grandchildren Erin Ingles, Latham Cohoon, and Evan Cohoon, and great-grandchildren Theory, Dare, and Silas Ingles. A memorial service will be at Trinity Episcopal Church in Jersey Shore on June 26, at 10:00 A.M., presiding will be Rt. Rev. Audrey Cady Scanlan. Participation is restricted to family due to COVID. Interment will take place at a later date at St. Anne’s Episcopal Church in Trexlertown, PA. Donations in memory of Father Cohoon may be made to Trinity Church, 176 Mount Pleasant Ave., Jersey Shore, PA 17740 Services are under the direction of the Yost- Gedon Funeral Home & Cremation Services, LLC, 121 W. Main St., Lock Haven. Online thoughts and memories can be made at www.yost-gedonfuneralhome.com and the Yost-Gedon Funeral Home facebook page.

Wayne Cornelius

Forthcoming in The Chronicles, newsletter of the UC San Diego Emeriti Faculty Association, Winter 2021 Engaging with Public Policy: An Immigration Scholar in Three Presidential Campaigns Wayne A. Cornelius My first dip into policy-relevant research came in 1975, and it was entirely serendipitous. I had been trained as a political scientist at Stanford to do survey research.

My dissertation project had been a survey study of political attitudes and behavior among residents of low-income neighborhoods of Mexico City, most of whom had originated in small rural communities. Five years later, I decided to study the rural-to-urban migration process from the front end, doing a survey study of high-emigration towns in the northeastern region of Mexico’s Jalisco state. When I got there I discovered that most the people leaving the region were not going to Mexican destinations but rather to the United States. Instantly, I became a student of international migration, and that became the focus of my research and teaching career. Shortly after I began publishing the results of my Jalisco field study, I was asked to write a policy memo for the Latin America staff of Jimmy Carter’s National Security Council, which had just begun to get interested in international migration issues. Based on that memo, I wrote an op-ed that was published by The New York Times. The article argued that Mexican migrants were more likely to be a net economic benefit to the country than a burden on taxpayers, drawing upon survey data that I had collected on migrants’ public benefits utilization and their contributions to tax revenues. Substantively, the focus of my policy-relevant research has been on how various kinds of immigration control policies influence individual-level decisions to migrate or to stay at home, with special attention to the efficacy and unintended consequences of tougher border enforcement. This was one of the perennial subjects of the field studies that my UCSD students and I conducted in rural Mexico from 2005-2015. We accumulated quite a large body of survey and qualitative data on this question – evidence that dovetailed nicely with what sociologist Douglas Massey and his Princeton-based field research teams were finding. Border management thus became my professional comfort zone.

I have advised three presidential campaigns on immigration and refugee issues. My first experience, in 2007-08 with Barack Obama, was disappointing. The chair of Obama’s immigration task force had reached out to me. We had many conference calls but there were no specific writing assignments. Most of the “asks” were intended to involve us in routine campaign tasks, like fund-raising and making cold calls to Iowa farmers. My ignorance of agricultural policy was profound and doubtless was revealed to each and every farmer with whom I awkwardly chatted. In hindsight, the Obama immigration advisory team was window dressing.

I sat out the 2016 election cycle, feeling no affinity with either Hillary Clinton or Bernie Sanders, and having convinced myself that Hillary would coast to victory. But in January 2019, when 37-year-old South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg began his improbable presidential bid, I jumped at the chance to be part of his historic candidacy. I had no contacts with Pete’s campaign staff, who at that time consisted of four full-time employees. I sent an over-the-transom email to the campaign’s general mailbox, offering my services and CV. Fortunately, an alert college student intern fished the email out and routed it to the policy issues staffer.

I soon discovered Rule #1 of campaign policy advising: “You never know enough, about enough subjects, to do this kind of work.” It was humbling to discover that, despite being a full-time immigration scholar for more than four decades, I knew so little about so many immigration-related issues that the campaign was concerned about. You need to be prepared to do a whole lot of new research, usually under considerable time pressure. I spent more time ploughing through on-line research sources during the Mayor Pete and Joe Biden campaigns than I had ever done before. I was constantly reaching out to other scholars who had done much more work than me on certain topics. One example: Before these campaigns I had always told anyone who asked, “I don’t do refugees!” But these campaigns were happening in the aftermath of the 2018 “migration crisis” at the border, which mostly involved asylum-seekers, not economic migrants. The Trump administration had taken aim at caravans, at asylum-seekers who were allegedly “gaming the system,” and it had implemented policies like “metering” and “Remain in Mexico” aimed at blocking access to the asylum process and making it more difficult to gain legal representation – not to mention the horrendous family separation policy, which was designed to deter would-be asylum-seekers. So, refugees were the elephant in the room, and I had to get up to speed quickly. I reached out to one of my former UCSD Ph.D. students, Idean Salehyan, who has become a national authority on refugee movements. I also sought advice from local-level NGO leaders, who were more likely than scholars to know what was happening on the ground. During the Buttigieg and Biden campaigns I was tasked to write or contribute to a total of two dozen full-length policy memos, each on a different topic – everything from options for modernizing our border ports of entry to combating human trafficking and creating a new culture of accountability in our immigration enforcement agencies. About which of these two dozen topics did I know enough, from the get-go, to write a decent policy memo? Perhaps one or two of them. I feel that I became a truly broad-gauge immigration scholar through my work in these campaigns. The bottom line is that you need to be willing to stretch yourself well beyond your usual bounds of professional competence. That’s often scary, but it can also be very rewarding. I mentioned the need for extensive Internet-based research. That was important not just to put data and ideas into my head but also to report that knowledge. Each policy memo was deeply sourced, and all sources had to be accessible on-line. Each memo included dozens of embedded URLs. Footnotes were definitely out—they take up too much space, and we were working within severe length constraints. The longest policy memo was supposed to be just 10-11 pages — even for huge, complex subjects like border management strategy. Issue briefs were typically three pages. There were many requests for one-pagers, consisting of talking points to be inserted in the candidate’s daily briefing book, input for public statements, and tweets to decry various anti-immigrant actions by the Trump administration. We were also asked to write op-eds, under our own name, to be published in major newspapers of battleground states. The one-pagers and 750-word op-eds illustrate another benefit of policy advising: It teaches you write with great parsimony. Strunk and White’s memorable advice – “Omit unnecessary words!” – was my mantra. Another important learning experience from the campaigns was deep-into-the-weeds “policy-wonkery.” I have never considered myself a policy wonk, but I came closer to becoming one during these campaigns. My previous forays into policy analysis had always involved evaluating existing policies – what had worked, what didn’t, and why. But designing new policies, trying to anticipate unintended consequences and potential obstacles to implementation – that was an entirely different kettle of fish. For each policy change that we proposed, a detailed timeline for implementation had to be laid out. What would President Biden need to do about this on Day 1? In the first 100 or 200 days? The first year? Making these finely calibrated distinctions required a lot of guesswork. For example, it’s fine to call for rolling back the odious “Remain in Mexico” policy. But how do you do that without provoking a new surge of asylum-seekers, before the capacity to control such a surge is fully in place? Still another key takeaway: Teamwork is essential in this kind of work. Most academic production is solitary, but policy advising is usually a team effort, requiring an elaborate division of labor. There were about fifty people contributing regularly to Biden’s working group on immigration. Only three of us were academics. The team was dominated by very smart people who had extensive, senior-level experience in the federal government during the Obama administration, especially in the Department of Homeland Security and in Department of Justice-related positions. Most had been trained as lawyers. For rapid response to Trump’s latest immigration outrage, we had a “legal swat team” to give us instant analysis of the legal issues raised by each policy development.

I quickly learned that to be effective, I needed to draw upon the skill sets and experience of the ex-government people on our team. Working with these folks was not always easy. One had to navigate around some very big egos. But there was real synergy, and the final product was always much better than it would have been if only academics had been involved. What happens when you disagree with the candidate on some issue? That did not happen during the Biden campaign, but it did occur once with Mayor Pete. The issue came up in one of the early primary debates, when the moderator asked a “Raise-your-hand-if-you-agree” question. The subject was decriminalizing unauthorized border crossings, which Julián Castro had been pushing most aggressively. All but two of the candidates raised their hands to support this idea (Joe Biden was not among them). When Pete’s hand went up, my at-home response was “Oh no!” I knew that the polling data showed that decriminalization was a non-starter with most Democrats and independents, and it would be a four-alarm fire in the general election — Trump would have attacked it non-stop as an “open borders” policy. But Pete had already taken the position, in a highly public forum.

So, how to get him to walk it back? First, I consulted with the legal eagles on Pete’s immigration advisory team. Their advice was: “Don’t try to change the statute – just change how it’s enforced.” That led me to think of an obvious walk-back strategy: Talk about changing prosecution priorities: Target serious felons and national security risks, rather than routine immigration offenses like unlawful entry or repeat entry by economic migrants and asylum-seekers. I wrote a memo entitled “Contextualizing Decriminalization,” which went through the legal arguments concerning Section 1325 of the Immigration and Nationality Act – the one that defines unauthorized entry as a crime. I summarized the relevant polling data and suggested several talking points for the walk-back. That was enough for Pete. He is super-smart and politically agile. He never again mentioned “decriminalization” as a policy prescription.

One final question: How much difference does policy advising make? What really happens to the products? Much of the time, the memos and talking points seemed to disappear Into a black hole. Feedback was rare. All of it had been requested by campaign staff, but, more often than not, It was hard to tell what specific use was being made of all this material. For whom were we writing? My position was that everything should be potentially useful to both the campaign staff (for speeches, debate preparation, tweets, etc.) and to the transition team – the people who would translate our ideas into policies once victory had been secured. As immigration receded into non-issue status in the contest with Trump, I concluded that I was writing mainly for the transition team.

One major exception to the pattern of limited feedback was a proposal that I developed for Mayor Pete — something that I dubbed a “Community Renewal visa.” In a nutshell, this was a new, place-based visa that would steer new refugees and other immigrants to specific counties that had been losing working-age population and whose public finances had been depleted by that population decline. The idea fit neatly into the “rural revitalization” plan that was being put together for Pete’s campaign. I developed a fairly elaborate implementation plan to go with the basic idea: What kinds of places would be eligible to receive CR visa-holders, what requirements would visa holders have to meet, the mechanics of matching visa-holders with destination communities, and so forth.

I sent the proposal up the campaign food chain, and less than three weeks later, I heard Mayor Pete advocate for it during a nationally televised primary debate. I nearly fell off my sofa! This idea was later folded into Biden’s plans for legal immigration reform and refugee resettlement. It was definitely my greatest hit of the 2019-20 election cycle. Wayne Cornelius is Distinguished Professor of Political Science and Gildred Chair in U.S.-Mexican Relations, emeritus, at UC San Diego. This article is adapted from a presentation to the graduate students of the Department of Sociology, UCLA, October 23, 2020.

Phillips Cutright

Phillips Cutright died on October 7, 2020. He was born in 1930 in Wooster Ohio to Drs. Clifford (Ph.D, Entomology) and Eva Goddin Cutright (M.D.). His parents and his aunt, Myrtle Goddin, made it possible for him to spend a summer working with the American Friends Service Committee to rebuild parts of the College Cevanol in Chambon sur Lignon, a small town in France which had sheltered Jewish children from the Nazis. After he returned to Wooster he served for a time in the US Air Force and then received his B.A from the College of Wooster, and went on receive a Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Chicago.

He was a faculty member at several colleges and universities, including Washington University of St. Louis, Dartmouth College, Vanderbilt University, and retired as a professor emeritus from Indiana University in 1994. He served as a member of boards of editors of a number of sociological journals and was a consultant to the Agency for International Development, the President’s Commission on Population Growth and the American Future, the Office of Education, and the Social Security Administration. He was the principal investigator on grants from the Social Security Administration, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, the National Institutes of Health, and the Center for Population Research.

He was also a research associate with the Harvard-MIT Joint Center for Urban Studies. He authored or co-authored over 130 articles in refereed social science journals and two books. He worked extensively with areal data — counties and states in the United States, and nations in cross-national comparative work. Several cross-national studies involved evaluation of the impact of family planning programs on fertility rates in less developed nations. A major study of the U.S. family planning program was the first evaluation of the U.S. program.

After retiring, he and his wife moved to western North Carolina where he continued his commitment to helping others by volunteering with various organizations including Habitat for Humanity, ECO, the Interfaith Ministry of Henderson County and the Henderson County Extension Service. He was an avid reader and loved gardening, art, classical music, travel, hiking, swimming and cooking.

He is deeply missed by his wife, Karen, and daughters, Anuschka and Jennifer Cutright, his sister, Juleene C. Tope, niece Laurel Tope and nephews John (Vanessa) and Drew (Debra) Tope, who will remember him for his kindness, generosity, commitment to the environment, insistence on fact-based research and support for progressive causes. Phill was a philanthropist, and it was important to him to do what he could to support environmental organizations such as The Nature Conservancy and organizations dedicated to serving others, particularly Planned Parenthood, Pisgah Legal Services of Asheville, the ACLU, PBS and NPR, and Compassion and Choices among others. Published on October 18, 2020

Peter Boeve

Peter Boeve was born on January 20, 1942 and passed away on January 20, 2021 and is under the care of Muehlig Funeral Chapel.

John K. Youel

Dr. John Kenneth Youel Jr. passed away at home on Thursday, July 1, 2021. Dr. Youel was born in Yonkers, New York, on June 24, 1934, and grew up in Irvington, New York, in Westchester County. His family moved to Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, and he attended high school at Cranbrook, graduating in 1952. He received his Bachelor of Science degree from the College of Wooster, Ohio in 1956 and received his Medical degree from the University of Michigan Medical School in 1960.

Dr. Youel completed his residency at Bellevue Hospital and Columbia Presbyterian Hospital. During his residency, he joined the United States Air Force and served in Wiesbaden, Germany where he completed two years of service. In 1967, Dr. Youel moved to Charlottesville, Virginia and began practicing General and Vascular Surgery at Martha Jefferson Hospital. Dr. Youel brought arthroscopic and carotid artery surgery to the Martha Jefferson Hospital and was an early adopter of laser surgery and cosmetic vein treatments.

Dr. Youel was also a man of many interests. He served as a Deacon and an Elder at First Presbyterian Church in Charlottesville. He was an avid sportsman with a passion for golf, skiing and horse riding, and was the President of the Virginia Walking Horse Association. In addition, he loved music – singing with the Opera Workshop, Virginia Oratorio Society, First Presbyterian Church Choir, and the Olivet Presbyterian Church Choir. Dr. Youel was also the Chairman of the Committee dedicated to fundraising and selecting the Casavant Freres organ for the First Presbyterian Church sanctuary. Dr. Youel took an interest in his family’s Scottish ancestry, and became an accomplished bagpiper; he was the Pipe Major of the Albemarle Highlanders Pipe Band, performing locally and competing at Scottish festivals.

He is survived by his wife, Sheila Tate; son, David Youel and his wife, Chrissy of Louisa; and daughter, Ellen Youel Ahmad and husband, Mazher, of Morristown, New Jersey; and his grandchildren, Jack and Maggie Youel and Sophia and Zakaria Ahmad. A visitation will be held from 6 until 8 p.m. on Wednesday, July 7, 2021, at Hill & Wood Funeral Home in Charlottesville, Virginia.

A service of worship and reception will be held at 12 noon, Saturday July 31, 2021, at Olivet Presbyterian Church on Garth Road in Charlottesville, Virginia, with Pastor Seth Lovell, A private interment will be held at Monticello Memory Garden. In lieu of flowers, donations can be made in Dr. Youel’s name to Olivet Presbyterian Church. Condolences may be shared online at www.hillandwood.com.

John C. Cochran

HAMILTON: John C. Cochran, 85, of Hamilton, NY, passed away on April 8, 2020, after a brief bout of pneumonia, not related to Covid-19. John was born on February 10, 1935 in Akron, Ohio, son of Harold and Irene (Snook) Cochran. John received a BA from the College of Wooster in 1957, a masters from the University of North Carolina in 1960 and a PhD from the University of New Hampshire in 1967. He met Ann Parrott in history class at the College of Wooster in 1955, and they were married in Stamford, Connecticut on August 2, 1958. Ann was a long-time Professor of Psychology at SUNY-Morrisville and predeceased John on March 21, 2010.

John’s distinguished career as a Professor of Chemistry at Colgate University began in 1966, and included serving as Chair of the Chemistry Department for multiple terms in the 1980s, as Acting Associate Dean of Students (1976-78) and as Colgate’s first Coordinator of Undergraduate Research (1991-94 and again 1998-99). John also received from Colgate the Phi Eta Sigma Teacher of the Year Award in 1987 and the Sidney J. and Florence Felton French Teaching Award in 1999. Beginning in 1994, he served two terms as Councilor for the Chemistry Division of the Council on Undergraduate Research, a national organization which encourages the development of faculty-student collaborative research programs at undergraduate institutions. John retired from Colgate in June 2001.

As a professor, John was known to his students for his 8:30am Organic Chemistry lectures, his thoughtful problem sets and his always-open office door. In his research, John focused on the synthesis of, and reactions involving, organic molecules containing tin (Sn) atoms, research that often involved undergraduates. During his career, John worked with over 100 research students, more than 40 of whom became co-authors with him on research articles published in chemistry journals. He also mentored many Colgate students who went on to become physicians and medical researchers. In the 1980s and ’90s, John mentored a cadre of young faculty who joined the then-expanding Chemistry Department at Colgate. His guidance, encouragement and patience helped foster their successful careers as teacher-scholars and leaders.

Outside the classroom and lab, John loved classical music and the Glimmerglass Opera, and was an avid and long-time member of the Colgate University chorus and the Hamilton College chorus. He also enjoyed cooking, tending to his vegetable garden, lawn and flowers (particularly rhododendrons), spending time on Lake Moraine, golf, traveling to many parts of the country and world, and being with other people. For almost four decades, John served as the guardian of the penalty box at Colgate hockey games. Surviving are his son Eric and daughter-in-law Stacy Cochran of New York City and his daughter Jill and son-in-law Joe Baker of Southlake, Texas; grandchildren Nina, Cindy and Pauline Cochran, and Mia and Joey Baker; seven nieces and nephews; and close family friends Merrill Miller and Ann Parkhurst. John was predeceased by his son Todd C. Cochran in 1980 and by his brother Robert Cochran in 2018. John greatly benefited in the last few years from expert and loving care from many, including Darlene Barrows, Kimberly Gunther and Edna Stoltzfus.

World events permitting, a celebration of John’s life will take place in the fall on a date to be announced. Contributions in John’s memory may be made to the Professor John C. Cochran Endowed Fund for Undergraduate Research in Chemistry, Colgate University, 13 Oak Drive, Hamilton, NY 13345. Interment will be at the Colgate Cemetery. Arrangements have been gratefully entrusted to Burgess & Tedesco Funeral Home, 25 Broad St., Hamilton, NY. To plant a tree in memory of John C. Cochran, please visit our Tribute Store.

Rodger Fink

ALBANY – Rodger L. Fink of Albany died August 28, 2021, attended by his beloved partner of 19 years, Laura Paris, and his younger brother Newt of Gloucester, Massachusetts. He was 78. Born in Rochester, he graduated from Binghamton Central High School and the College of Wooster in Wooster, Ohio. He earned an M.A. in English literature at Syracuse University. A great lover of music, he played in school musical ensembles, sang in school choruses, and continued singing for many years, including with the Albany Pro Musica Masterworks Chorus.

During his student years he vigorously opposed the Vietnam War and was not ultimately drafted. Rodger taught English literature at Siena College and at St. Joseph’s prep in Montvale, N.J. where he also very much enjoyed coaching the boys’ soccer team. Following studies in labor relations at Pace University he accepted a position with the N.Y. State Teachers’ Retirement System, providing retirement planning services to teachers and developing web applications for that system.

Rodger was a lifelong reader and student of history, philosophy and literature. Thoughtfully opinionated, he was eagerly engaged in almost any topic with old and newly-met friends at his favorite Starbucks. He enjoyed being outdoors, hiking in the Catskill and Adirondack mountains, canoeing and kayaking. He cycled the Erie Canal trail, around Lake Champlain and on a winter coastal route from New Orleans to Mobile. He also enjoyed learning home building skills, auto repairs and gardening. His many hobbies included tropical fish, model trains, astronomy, N.Y. Times puzzles, listening to great music, and, as mentioned, singing.

After retirement, Rodger volunteered with the Mohawk Hudson Land Conservancy, the Alzheimer’s Association of Northeastern New York, and Community Hospice. His physical activities decreased during the years after the discovery and removal of a tumor in his spinal column. Undaunted, he learned to drive with hand controls and continued to cycle for a decade. He showed great resilience through many surgeries and orthopedic procedures and a continuing battle with pain and spasms from nerve damage. He required a wheelchair for the last several years. The family is grateful for the support of friends throughout the years, for the many caring professionals who attended to his medical needs and to the staff members of Community Hospice who provided care at home and at the Hospice Inn at St. Peter’s Hospital. Rodger is survived by his partner Laura Paris; his brother Newton Fink Jr.; his sisters, Cynthia Fustukjian of Santa Cruz, Calif. and Ruth Fink of Baldwinsville, N.Y., two nephews, three nieces and nine progeny extending the line. His faithful cat, Kit, is keeping his chair warm. When the extended family and friends can assemble, and COVID-19 threats diminish, we will gather in memorial at the First Unitarian-Universalist Society of Albany.

Robert B. Everhart

Robert B. Everhart, Ph.D, our beloved friend and mentor, passed away in Portland July 10, 2021 due to complications from dementia. He was the longest serving Dean of the College of Education at Portland State University (1986 – 1998). Bob was born in Pittsburgh, Pa., Oct. 25, 1940 and grew up in the country near Gibsonia, Pa. His father worked as a patent attorney for Dupont Chemical and his mother was a homemaker who cooked the best Polish dishes ever. During the summers Bob worked on his grandfather’s farm. Being the youngest of five cousins, his job was to clean out the barn. He later worked on the Penn RR’s to earn money for college.

Bob attended Wooster College in Ohio and upon graduation in 1962, he signed up for the Navy’s OCS school. He graduated as an Ensign and was deployed to Vietnam on the carrier, USS Ranger. After four years he safely returned to Alameda, Calif.; then moved to Eugene, Ore., as a reservist and took advantage of the G.I. bill at the University of Oregon. He taught in middle school there as he worked on his doctoral degree. After receiving his Ph.D in 1972, he moved to Puyallup, Wash., to work for the NW Educational Research Lab and the University of Washington. Soon after he was hired by the University of California at Santa Barbara, as an Asst. Professor of Education, then full Professor, and remained there for 10 years. In 1986, he became Dean of the School of Education at PSU and served until 1998.

As Professor Emeritus, Bob continued teaching until 2004 in the Sociology Department and also as an advisor in GSE’s doctoral program. He was most proud of instituting a fifth year Master’s program for teachers and a Doctoral degree program, thus renaming PSU’s SOE, the Graduate School of Education. Secondly, he helped initiate the Portland Teacher’s Program (PTP), for disadvantaged and minority students, interested in teaching careers. The program guided students through middle school, high school, then onto community college with financial assistance, and ultimately to PSU for their teaching degree. At Bob’s last PSU graduation ceremony in 1998, President Clinton gave the Commencement address and he singled out two graduates from Dean Everhart’s PTP program for recognition and applause. Lastly, with his interest in the Sociology of Education, Bob authored and co-authored many books and refereed articles on educational policy, ‘at risk’ youth, ethnographic research, and navigating school change.

Bob was easy going, outgoing and loved the outdoors. He took his daughters hiking and backpacking at an early age, and they have become environmental stewards ever since. He met Shelley (his second wife) in Santa Barbara, Calif.; they married in 1987 and settled in Portland. They joined the Mazamas, climbed many N.W. glacial peaks and participated in numerous backpacking trips. There wasn’t a mountain lake that they didn’t jump into! Bob and Shelley ran 10K’s, Hood to Coast, biked Cycle Oregon, skied with the Cascade Prime Timers, kayaked in Sea of Cortez, and cycled in Europe. They traveled the world – from Turkey to New Zealand, Europe to Patagonia, Alaska to Costa Rica, Russia to China, the Caribbean to Tahiti – you name it – what a beautiful, adventurous life they shared! Bob is survived by his loving wife, Shelley; his daughters, Ina Everhart, Nyssa Everhart and Toby Everhart; and three grandchildren, Lea, Gavin and Willow, all of N. Seattle; his sisters, Martha Fahlberg of Raleigh, N.C., and Mimi Simmons of Tucson, Ariz.; and wonderful in laws – John, Rick, Carol, Vicky and “brother” Brad.

A memorial service will be planned at a later date when it’s safe to travel and gather at St. Luke Lutheran Church as well as a Celebration of Life at PSU. In lieu of flowers, please consider a donation in memory of Bob to PSU’s: College of Education Pathways for Diverse Educators (Fund # 8300120), payable to PSU Foundation, P.O. Box 243, Portland, OR 97207; or donate to the Alzheimer’s Association at alz.org/give. Online condolences may be sent to: https://crowncremationburial.com/tribute/details/19535/Robert-Everhart/obituary Please sign the online guest book at www.oregonlive.com/obits Published by The Oregonian from Aug. 20 to Aug. 22, 2021.

James L. Cooper

James Louis Cooper Sr., a professor emeritus of history at DePauw University and a widely recognized expert on the study and preservation of Indiana’s historic bridges, died on August 19, 2021. He was 86 years old. Son of James H. and Gladys Wambaugh Cooper, the Princeton, N.J. native moved to Greencastle in 1964 to join the faculty of DePauw University, where he served for more than three decades. At DePauw, Cooper was dedicated to faculty development, becoming the university’s academic dean in 1981 and then vice president of academic affairs in 1983. But what he valued most was engaging with his students. “Jim was an exceptional classroom teacher who became a lifelong friend,” said Richard Dean, DPU Class of 1970. “He was a wonderful mentor to me and many others. He was fun to be around. He had an authentic laugh, which I will never forget.” Cooper’s interests and skills ranged widely. As a youth, he mastered the art of tree surgery working for his father’s tree service business. He was one of the “high flyers,” climbing into upper tree limbs to trim and prune. Cooper left Princeton to attend the College of Wooster in Ohio, where he edited the college newspaper The Wooster Voice and graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1956. There he met Sheila Roberta McIsaac, his wife of 64 years, whom he married on the same day that she graduated. They went on to co-author a book in 1973, The Roots of American Feminist Thought, an anthology of works written by feminists over the past two centuries. A Danforth Graduate Fellow, Cooper received his MA and PhD from the University of Wisconsin, Madison. His academic interests ranged from the American revolution to urban planning, but his passion ultimately rested with cataloguing, studying and preserving Indiana’s historic bridges. For years, he tirelessly worked to document those bridges in a database that now serves as a resource for the historic preservation community. In retirement, Cooper traveled daily to a cabin in the woods where he wrote Artistry and Ingenuity in Artificial Stone: Indiana’s Concrete Bridges, 1900-1942 and Iron Monuments to Distant Posterity: Indiana’s Metal Bridges, 1870-1930. His contributions to the field were recognized with several awards, including the Indiana Historical Society’s Dorothy Riker Hoosier Historian Award. Cooper’s work captured his appreciation for the culture, ingenuity and journey of the people who built, crossed, and settled around the bridges that he so admired. Cooper relished good stories, whether they were in the classroom with his students, in the kitchen with friends and family, or on the road with bridge enthusiasts across the Hoosier state. Cooper is survived by his wife Sheila Cooper; daughter Mairi Cooper (husband Matthew Pierce); son James L Cooper Jr. (wife Dina ElBoghdady); granddaughters Sarah and Claire Cooper; and brother Barry Cooper (wife Joan). Due to Covid, no memorial service is planned at this time. A burial service will be held at a later date at Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn, NY. Fond memories and expressions of sympathy may be shared at www.hopkins-rector.com for the Cooper family.

Frances Ann Walker

When Ann Walker and I (Ellie Thomson Adman) graduated from Wooster in 1962 there were five of us, woman chemistry majors- the other three are Helen Li (Tochen) who became an MD, Rachel Abernathy who also became an MD, and Jayne Bennett (Mortenson) who became a research librarian. Ann and I chose research in academia, and both of us had PhDs.

Frances Ann Walker was a world-renowned chemist, a wonderful mentor, well-respected teacher, and a role model, especially for women, many of whom followed in her professional footsteps. Ann, as her family, friends, students, and colleagues affectionately called her, was born and raised in Adena, Ohio, the oldest of five siblings. She graduated from Adena High School in 1958.

She attended the College of Wooster where in addition to her studies, she played clarinet in the College of Wooster Scot Marching Band. She received her B.A. in Chemistry there in 1962 along with four other women classmates, who have remained in contact throughout their lives, and her Ph.D. in Inorganic Chemistry from Brown University in 1966. She started her academic career with a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of California, Los Angeles, which was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Thereafter, she became Assistant Professor of Chemistry at Ithaca College in 1967 and three years later moved back to California to join the Faculty at San Francisco State University. Excelling in both research and teaching, Ann was rapidly promoted to Associate Professor of Chemistry in 1972 and to Professor of Chemistry & Biochemistry in 1976. After developing a successful research program in porphyrin and iron porphyrin chemistry, Ann moved to Arizona in 1990 to join the Faculty in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at the University of Arizona, where her research program expanded to include heme protein structure and function. Ann’s prolific career at the University of Arizona was rewarded with promotion to Regents Professor in 2001. In 2013, Ann retired as Regents Professor Emerita.

Ann’s novel findings in model heme and heme protein chemistry, which sparked a new era in the field of paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, resulted in the publication of more than 170 peer-reviewed papers, 19 chapters in books, and hundreds of published conference proceedings and abstracts. Ann’s remarkable work was recognized by numerous prestigious awards. To name a few, in 2000 she was awarded the Francis P. Garvan-John M. Olin Medal which recognizes female chemists for distinguished scientific accomplishment, leadership and service to chemistry. In 2006 she was awarded the Alfred Bader Award in Bioinorganic or Bioorganic Chemistry for her contributions to the field of bioinorganic chemistry. In 2020, she received the Eraldo Antonini Lifetime Achievement Award from the Society of Porphyrins and Phthalocyanines in recognition of her exceptional, internationally acclaimed research on heme proteins and metalloporphyrins. Ann’s contributions to chemistry were also celebrated by her election in 2011 as Fellow of the American Chemical Society in recognition of her outstanding achievements and contributions to science, the profession and the Society, her excellence in scientific leadership and her exceptional volunteer service to the scientific community. Ann was also elected to serve (1998-2010) as Associate Editor for the prestigious Journal of the American Chemical Society, the flagship journal of the American Chemical Society.

Ann was a ferocious worker with what seemed like a limitless reservoir of energy. Her research program, supported by the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation, focused on investigating the electronic structure, bonding, thermodynamics, and kinetics of hemes and other metallomacrocycles. Whereas Ann’s early work concentrated on the understanding of synthetic porphyrins and their iron complexes, she later incorporated the tools of recombinant DNA technology to expand her research interests to include heme proteins and the enzymatic reactions these molecules carry out in living organisms. Her fundamental discoveries in porphyrins and related iron complexes paved the way for her and others to study and understand how heme, an iron porphyrin complex present in many important heme containing proteins, enables the remarkable and central role these proteins play in living cells.

Ann also was a caring and remarkable mentor for uncounted undergraduate, graduate and postdoctoral students she mentored, all of whom are pursuing rewarding professional careers either in academia or in industry. Her influence on female scientists and students from underrepresented groups was notable. Ann led and mentored by example. Her passion for research and education, driven by her impeccable professionalism and her strikingly intelligent, conscientious, and quiet manner earned her the respect and love of her students and colleagues alike. Everyone fortunate enough to have had Ann as mentor and friend is indebted to her for having enriched and furthered their own scientific careers. Ann lived her life fully and with the certainty that she would leave this world a better place.

Ann married Frederick R “Fritz” Jensen, an organic chemistry professor at the University of California Berkeley in 1976, and they had many adventures until his death in 1987 after a long illness.

Ann was always very involved in her church. She was an elder at Trinity Presbyterian Church in Tucson, serving on the session for several terms during her 30 years there. She also was a very active member of the pastoral search committee when it was needed on several occasions, taking this role very seriously. Additionally, she served on the Presbyterian Campus Ministry Board.

Ann loved to travel. She often combined interesting trips with chemistry conferences and symposia. She did sabbaticals in England, Germany, and Argentina and made regular trips to Luebeck, Germany to perform Moessbauer spectra in the lab of Alfred Trautwein. She traveled to interesting places all around the world, including Russia, many European countries, Machu Picchu in Peru, China, Japan, Australia, and the high mountain Atacama observatory and desert in Chile. She traveled to all 8 continents (including Madagascar), often including family members. She took sister Janet (age 15) to Europe in 1970 for a month, cementing the travel bug in her too. Ann and Fritz bought land in Panajachel, Guatemala on the scenic high mountain Lake Atitlan and built a house there. Several family members including Bob and Janet visited them when they were there at Christmastime or in the summers, having many adventures. Ann and Fritz visited brother David in Alaska in 1976. Ann, Janet and Janet’s wife Kathy traveled together to Antarctica in 2014, and Ann and sister Betty took a four month cruise around the world in 2019.

Ann died on Jan 30, 2022 after a long illness. Donations in her name can be sent to Trinity Presbyterian Church in Tucson: http://trinitytucson.org

Paul E. Davies

It is with great sadness that we announce the death of Paul Ewing Davies Jr. of Chicago, Illinois. Paul was born and raised in Chicago and passed away on July 20, 2021, at the age of 87. Paul was born on December 13, 1933 to Paul Ewing Davies, Sr. and Marjorie Billings Davies and is predeceased by his sisters Midge Smith and Katie Siege. He was predeceased by his two sons, Todd Olson Davies and Tanner Olson Davies. He is survived by his daughter, Tika Walsh (Kevin) and his son Kenneth E. Davies (Brenda); and his grandchildren, Tanner Walsh, Reilly Walsh, Cameron Walsh and Lauren Davies. Paul graduated from Francis Parker School in Chicago, the College of Wooster, where he was awarded his BA, and Yale University, where he received his Master’s Degree in international relations. He proudly served in the United States Army from 1955 to 1957. Paul had a career in banking and corporate communications. Paul was an avid supporter of the City of Chicago, fan of WFMT radio station, the Chicago Cubs and was a committed member of Christ Church in Winnetka and later Fourth Presbyterian church in Chicago, having loved their communities and music programs. After retiring, he thoroughly enjoyed working at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Sears (Willis) Tower. Paul most loved spending time with friends and family and will be missed by many. Memorial service will take place Friday, August 20, 2021, 11:00 a.m. at Christ Church Winnetka, 784 Sheridan Road, Winnetka, 60093. Info: donnellanfuneral.com or (847)675-1990. To send flowers to the family or plant a tree in memory of Paul Ewing Davies please visit our Tribute Store.

Bernard B. Davis

Davis, Bernard B., M.D. of St. Louis, Missouri, passed away peacefully on September 4, 2021 surrounded by family. Bernie was born in Parkersburg, West Virginia on September 12, 1932 to Katharyn (Shannon) and Bernard B. Davis Sr. He was a graduate of the College of Wooster and the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. He served our country in the Armed Forces and was a veteran of the Korean War. He is survived by his beloved wife of 65 years, Leila (Staub), his four children, Katharyn (Michael Fenwick), Elliot (Beth Wright), Laura (Todd Oberman) and Sharon Fenoglio (Domenic), and his sister Karen Mascaro. He was “Poppy” to eleven grandchildren, Cary Stroup, Bonnie Stroup Basler (Christopher), Andrew Stroup, Wesley Davis (Olaitan Awomolo), Alan Davis (Sarah Nydes), Brett Davis, Joshua Oberman, Nina Oberman, Kira Oberman, Isabel Fenoglio, and Domenic Fenoglio, and five great grandchildren, Max, Raven, Elliot, Cliff and Leila. He was preceded in death by his sister, Dianne Dencler. He was a cherished uncle to seven nieces, great nieces and nephews. He will be greatly missed by his many cousins, friends, colleagues and neighbors. In lieu of flowers, donations are appreciated to the Staub Davis Mission Fund, Faith Des Peres Presbyterian Church, 11155 Clayton Road, St. Louis, Missouri 63131, or CHIPS Health and Wellness Center, 2431 N. Grand Blvd, St. Louis, Missouri 63106. Services: A memorial service will be held at Faith Des Peres Presbyterian Church on September 18, 2021 at 2 pm. Please see BoppChapel.com for more information. Published by St. Louis Post-Dispatch on Sep. 12, 2021.

Thomas W. Fletcher

Thomas W. Fletcher, 93, passed away peacefully with his loving wife by his side at First Health Hospice House in Pinehurst on June 28, 2021. Tom was born March 8, 1928, in New Castle, PA to Isaac and Margaret Lucas Fletcher. He graduated from New Castle High School in 1946 and joined the US Army shortly thereafter. His assignment took him to the northern region of Greece (Salonica) at the time of that country’s civil war. Upon discharge, he pursued his further education at Wooster College, Wooster OH, graduating with honors in 1951. He chose Washington DC to find employment with the US Government, while attending George Washington University Law School night classes where he obtained his law degree in 1960. He was admitted to a well-established law firm specializing in communications law before the FCC and, over a 30-year career, represented hundreds of clients across the country. Tom was recognized as a lead attorney in his field and several clients became lifelong friends. The groups enjoyed several golfing trips to the various courses in Scotland. He recalled those trips with fond memories. Upon retirement in 1990, he kept busy accompanying his wife, Connie, on antiquing hunts for the shop that she had established in Leesburg VA. His friends got a kick out of this, but the pursuit became a joy for the two of them and he especially liked finding antique furniture in need of refurbishing. After 15 years, they decided to close the shop and relocate, choosing Southern Pines as their next destination. Moving into the community of Talamore, they met many new friends with whom Tom enjoyed playing golf for several years to come. Tom was a member of Pinehurst United Methodist Church. Tom was a good soul, a wonderful man greatly loved by his family and friends. He is survived and cherished by his wife of 38 years, Connie; his stepdaughter, Christi (Rick) Geist of Pinehurst; his stepson Rick (Tracy) Fath and step grandsons, Hunter and Levi, and step granddaughter, Miriam of Elkins WV; and step granddaughter Lauren (Gavin) Duckworth and her family of Morganton NC. He was predeceased by his parents and his brother, Robert, of New Castle PA. A celebration of Tom’s life will be held on July 24, 2021, at 10:00AM at Pinehurst United Methodist Church, 4111 Airport Road, Pinehurst, with Pastor Katie Tomlin officiating. In lieu of flowers, the family requests consideration of donations to Pinehurst United Methodist Church or First Health Hospice Foundation, 150 Applecross Road, Pinehurst NC. The family would like to extend their sincerest gratitude to the staff at Hospice House in their care of Tom in his final days. Services arrangements have been entrusted to Boles Funeral Home. To send flowers to the family or plant a tree in memory of Thomas William Fletcher please visit our Tribute Store.

Richard P. Hervey