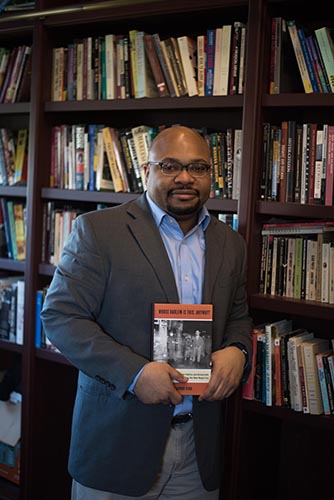

Shannon King honored by National Council for Black Studies

WOOSTER, Ohio – When Shannon King was growing up on 118th St. and Madison Ave., near Mount Morris Park in Harlem, the neighborhood bore little resemblance to the semi-mythical place once inhabited by Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, James Weldon Johnson, and others, during the period between World War I and the Great Depression that became known as the Harlem Renaissance.

“People’s view of Harlem in that period is locked into a particular aspect – the artistic and literary,” says King, associate professor of history at Wooster, and little scholarly attention has been devoted to “the basic, bread-and-butter, working class issues” of how people made a living, where they lived, or how they struggled against discrimination and violence. And so in graduate school, he found himself being drawn to examine Harlem between the wars, “not as a cultural and intellectual hub, but as an urban space,” like any other.

The result was a dissertation that later served as the foundation for King’s first book, Whose Harlem Is This Anyway? Community Politics and Grassroots Activism During the New Negro Era. Published last year by NYU Press, the book was recently named this year’s Outstanding Book in Africana Studies by the National Council for Black Studies.

The book, King writes in his introduction, “spotlights black grassroots activism around local issues – work and unionization, high rents and housing conditions, leisure life and vice activity, and police brutality and self-defense.” The issues may have been local, he notes, but just as, in hindsight, people saw the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955-56 as foreshadowing the larger civil rights movement of the 1960s, local activism in the Harlem of the teens and twenties “was a dress rehearsal for political mobilization in the 1930s and 1940s.”

In his research, King relied heavily on contemporary black newspapers like the New York Age and the Amsterdam News, comparing their coverage of events in Harlem with mainstream, white press coverage of the same events; NAACP and Urban League archives; local government records; and oral histories of Harlem residents like labor leader and civil rights activist A. Philip Randolph and Samuel J. Battle, New York City’s first black police officer.

To have the book win national honors “is amazing and humbling,” King says. “And the fact that two historians I respect tremendously ‘blurbed’ the book was almost as exciting as being published.”

For his next project, King is looking at how New York City’s black community struggled with issues of inter- and intra-racial crime and police brutality in the period between the riots of 1935 and 1943.

King says that perceptions of, and scholarship on, the Harlem of the first half of the last century have tended toward one of two extremes: Harlem as mecca, or Harlem as ghetto. His goal is “to try to tell a more complicated story about Harlem that appreciates the cultural and intellectual dimensions, but also recognizes the worsening conditions and people’s attempts to address them.”

Posted in News on May 2, 2016.