Christina Welsch’s book offers fresh perspective on East India Company’s collapse

Christina Welsch, associate professor of history and South Asian studies at The College of Wooster, is the author of a book that flips India’s traditional historical narrative about colonial India, shifting focus from the northeast to south India where the importance of the armies and soldiers to the understanding of India’s social and political history becomes clear.

The Company’s Sword: The East India Company and the Politics of Militarism, 1644-1858, was published in August 2022 by Cambridge University Press. The book, which extends Welsch’s dissertation research, is a belated answer to a student’s question during a spring 2017 British Empire class she taught her first year at Wooster. During the class, she explained that until 1857 the British territory in India was controlled by the British East India Company, not by the British crown. The company had its own private army separate from the British army, and the majority of the soldiers were Indian soldiers, called sepoys.

“A student asked me, ‘Why did the East India Company army survive when other private armies in the British Empire had disappeared before then, and why did it fall apart after 1857?’ I realized I had never seen that framing before. It was an interesting way to think about some of the themes of my dissertation to make them more substantial or book-worthy,” Welsch said.

In the book, she described the 18th century political and military landscapes in south India, especially when the British empire was expanding its reach into India. Welsch explained how the East India Company’s army had “a unique role in India, not just as a tool of conquest and expansion but as the structure and institution through which a lot of diplomacy took place.”

By the 1800s, the company’s army was the central mechanism of rule; however, there was also a level of anxiety because more than 90 percent of the army was Indian soldiers, who were viewed as unreliable. Welsch pointed out how white officers who were in command positioned themselves by using that anxiety and reliance. They gained considerable power in the government of the East India Company by declaring how the company was dependent on the army, and the officers’ command was the only thing keeping the sepoys loyal. “Other historians have already shown that white military officers held far more power than military officers in other parts of the British Empire, but my book is the first to show how that power emerged out of the unique political landscape of colonial India.” she said.

The officers’ power collapsed in 1857, when sepoys led a large rebellion in the north, which proved that the company’s army was not able to maintain the loyalties and stability of the sepoys. The catastrophic event for the British Empire was also the downfall for the East India Company.

Welsch drew on some of her dissertation research for The Company’s Sword, her first published book. She supplemented the dissertation research with further work completed with funding from Wooster’s Isabel and Elizabeth Ralston Presidential Endowment for Faculty Development. Her research included travel to London, Scotland, and two south Indian cities: Chennai and Hyderabad. She used British and East India Company sources as well as documents written in Mughal Persian, similar to modern-day Farsi. The Mughal Persian sources provided access to political records from Indian states that were encountering the East India Company and allowed her to better understand the context of the company’s operations in south India.

Two Wooster undergraduates at the time helped with the research, Georgina Tierney ’22 and Cat Long ’21, and their names were included in the book. Tierney read material from the 1600s to identify what jobs were done by a category of workers the British referred to as peons. “I wanted to find out more about their roles in the early East India Company, so Georgina culled through the records. Anytime a peon showed up, she documented what they did, to give me a better sense of their jobs.”

Long looked at newspaper articles after 1857 to find out if East India Company officers complained about the company being dissolved. “I knew there were a lot of complaints, but I wanted to know were the officers still using the rhetoric, ‘We are the only people who can preserve the imperial stability.’ Cat found evidence that they were. In addition to me trying to draw materials of my research into the classes that I am offering, I think it’s great that Wooster gives me the chance to bring undergraduate students into the research project,” Welsch said.

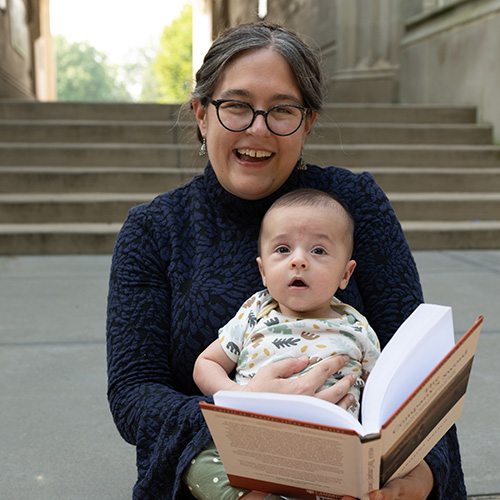

Image above: Welsch reads The Company’s Sword: The East India Company and the Politics of Militarism, 1644-1858 with her son Elliott, who arrived so close in time to the book to be almost “twins.”

Posted in Faculty, News on September 21, 2022.

Related Posts

Related Areas of Study

South Asian Studies

One of the few programs in the country dedicated to the history and culture of South Asia

MinorHistory

Critically examine events and societies of the past and learn to tell the stories future generations need to know

Major Minor