Rick Lehtinen Examines the Frequency of One of Wooster’s Trademarks—the Black Squirrel—in Recent Study

WOOSTER, Ohio – Many first-time visitors to The College of Wooster campus are quite taken by the sight of black squirrels scurrying around the grounds, and some even consider the cute-looking critters an unofficial mascot of sorts, but how rare are they? That’s, in part, what Rick Lehtinen, professor of biology, set out to find in a recent study that was published by Ecology and Evolution.

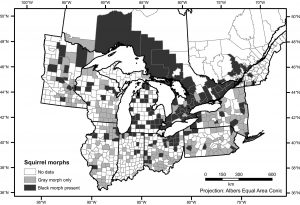

Lehtinen and a team of students utilized a variety of methods to map out the color frequencies of Scirus carolinensis, the scientific name of the eastern gray squirrel. The gray squirrel is not always gray, but also can be entirely black (melanistic) or even all white (albino or leucistic). The area included in the study includes the Great Lakes region, the state of Ohio, and more intensely within Wooster and its surrounding region.

A map of the geographic distribution of the gray and black color morph of the eastern gray squirrel in the Great Lakes region, based on 4,678 citizen science records from iNaturalist.org. (graphic courtesy of Rick Lehtinen)

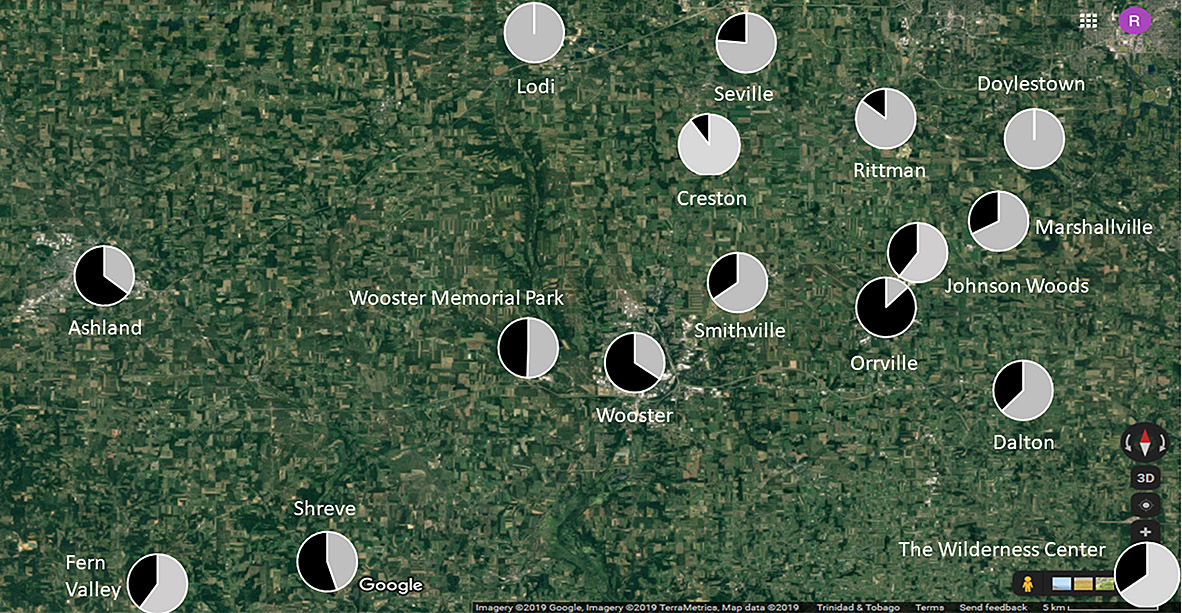

The underlying conclusion was that black squirrel populations are pretty common and widespread throughout the Great Lakes region, however, they are often localized. For example, where the most intensive surveys were done, 65-70 percent of the gray squirrel population in Wooster were black while just to the east in Orrville saw a 90 percent rate, but in Lodi, a few minutes north of Wooster, the black squirrel population was 0 percent (100 percent gray).

In this map of the region surrounding Wooster, Ohio, each pie shows the proportion of gray morph (light shading) and black morph (dark shading) squirrels, as observed in that population. (graphic courtesy of Rick Lehtinen)

How could there be such a wide variance in the color morph within just a few short drives? According to Lehtinen, “these patterns are suggestive of genetic drift as an important mechanism of evolutionary change.” Genetic drift is defined as the influence of random events of the frequency of gene variants.

“Our initial expectation was that squirrel fur color would matter a lot and that we would see consistent patterns from year to year and place to place. But because the frequency of black versus gray varies so much from place to place, we ended up concluding that genetic drift—a random mechanism of change—had to be involved,” explained Lehtinen.

Lehtinen added this is a “story that’s continuing to unfold,” as he plans on continuing the research and collaboration. Other variables under immediate consideration are how temperature and the weather, specifically a harsh winter versus a mild winter, and the size of acorn crops may be impacting the color morph of the squirrel population.

“This is a study of evolution in action. We have some squirrels that have one trait (black), others have another trait (gray). We know that it’s a genetically determined trait, and if it changes overtime, that’s evolution,” said Lehtinen. “Evolution is happening all around us, right under our noses. It takes some patience to count and document 80,000 squirrels, but research such as this is central to understanding what is happening in the natural world.”

In order to track 80,000 squirrels and compile the data, Lehtinen received plenty of assistance from fellow faculty member Brian Carlson, Wooster students Alyssa Hamm, a senior, and Alexis Riley, a junior, as well as recent graduates Weston Gray ’19 and Maria Mullin ‘18, all of whom were co-authors on the paper. The data came from a variety of sources, ranging from local field surveys with wildlife cameras and Lehtinen’s squirrel counts on his daily walks to and from campus to citizen science data, such as the iNaturalist database and hunter records from the Ohio Natural History Database.

Posted in Faculty, News on February 20, 2020.

Related Posts

Related Areas of Study

Biology

Explore molecular and cellular biology, ecology and more with top faculty and access to extensive lab facilities.

Major Minor